Building User Search for a Decentralized Messenger

by jgmontoya

User search should be simple. Someone types a name, you show matching profiles. On a centralized app this can be done easily without even thinking about it.

Building it for White Noise, a decentralized messenger built on Nostr and MLS, took three iterations and roughly 4,000 lines of Rust before it felt right.

Why Search on Nostr Is Hard

In Nostr, user profiles are events. Specifically, kind:0 metadata events published to relays. There’s no central user table. No index. No SELECT * FROM users. Profiles are scattered across dozens of relays, and any given relay might have outdated data, partial data, or no data at all for the person you’re looking for.

Nostr does have NIP-50, a search capability that lets you send a text query to a relay and get back matching events ranked by relevance. But relevance according to whom? The relay has no idea who you are, who you follow, or who you’ve talked to before. It returns whatever it thinks is a good match from its own index. For a messenger where you’re trying to find your people, not just any people, that’s not useful. You’d end up scrolling past strangers to find the friend you already know exists on the network.

So I had to build our own. This creates a few problems that aren’t obvious at first:

-

No single source of truth. The same user might have different metadata on different relays. Which one is canonical? The one with the latest timestamp, but you have to fetch from multiple relays to know that.

-

No ranking signal. When you search “Alice,” you might get hundreds of results. In a centralized app, you’d rank by follower count, mutual friends, activity. On Nostr, none of that data is pre-computed. You’d have to fetch each user’s follower graph to rank them, which means more relay queries.

-

Your social graph matters, but you don’t have it. You almost always want to find people you know, or people your friends know. But your follow list is just a list of pubkeys. You don’t have their profiles cached locally, and you definitely don’t have your follows’ follow lists.

-

Relays are slow and unreliable. Some respond in milliseconds, some in seconds, some not at all. If your search blocks on the slowest relay, the UX is terrible.

The First Attempt

My first implementation attacked the problem head-on. I built:

- A

CachedGraphUsertable in SQLite to store profiles locally with a 24-hour TTL. - A graph traversal system that walked your social connections: contacts first, then follows-of-follows.

- A metadata matcher that scored results against the search query by name, display name, and NIP-05 identifier.

- A background cleanup task that pruned stale cache entries.

The approach was straightforward: start from your follows, fan out to their follows, fetch metadata for everyone, match against the query, stream results as they come in.

// Simplified for clarity. The real code handles timeouts, cancellation,

// batch processing, and caps per radius.

for radius in radius_start..=radius_end {

let layer_pubkeys = fetch_follows_from_layer(&previous_layer).await;

for pubkey in layer_pubkeys {

let metadata = fetch_metadata(&pubkey).await; // network call per user

if let Some(result) = match_against_query(&metadata, &query) {

tx.send(SearchUpdate::ResultFound(result));

}

}

previous_layer = layer_pubkeys;

}

Simple BFS. For each radius, expand the graph one hop, then check every pubkey against the query. A network call per user to fetch their profile, for potentially thousands of users.

It worked. You could type a name and get results. But “worked” is generous.

The problems showed up immediately in testing:

- Painfully slow. Even searching for people close in your social graph took forever to return results and the phone would get noticeably hot.

- Crashes. On some phones, the search would just crash the app.

- No performance visibility. I had no idea where time was being spent. Was it relay latency? Graph traversal? Matching? I was debugging blind.

The Rebuild

Look at the v1 loop again: while it’s fetching follow lists to expand the graph, it’s not fetching metadata to resolve matches. And while it’s fetching metadata, the graph isn’t expanding. Even with batches, everything is sequential. The phone is either doing graph work or match work, never both.

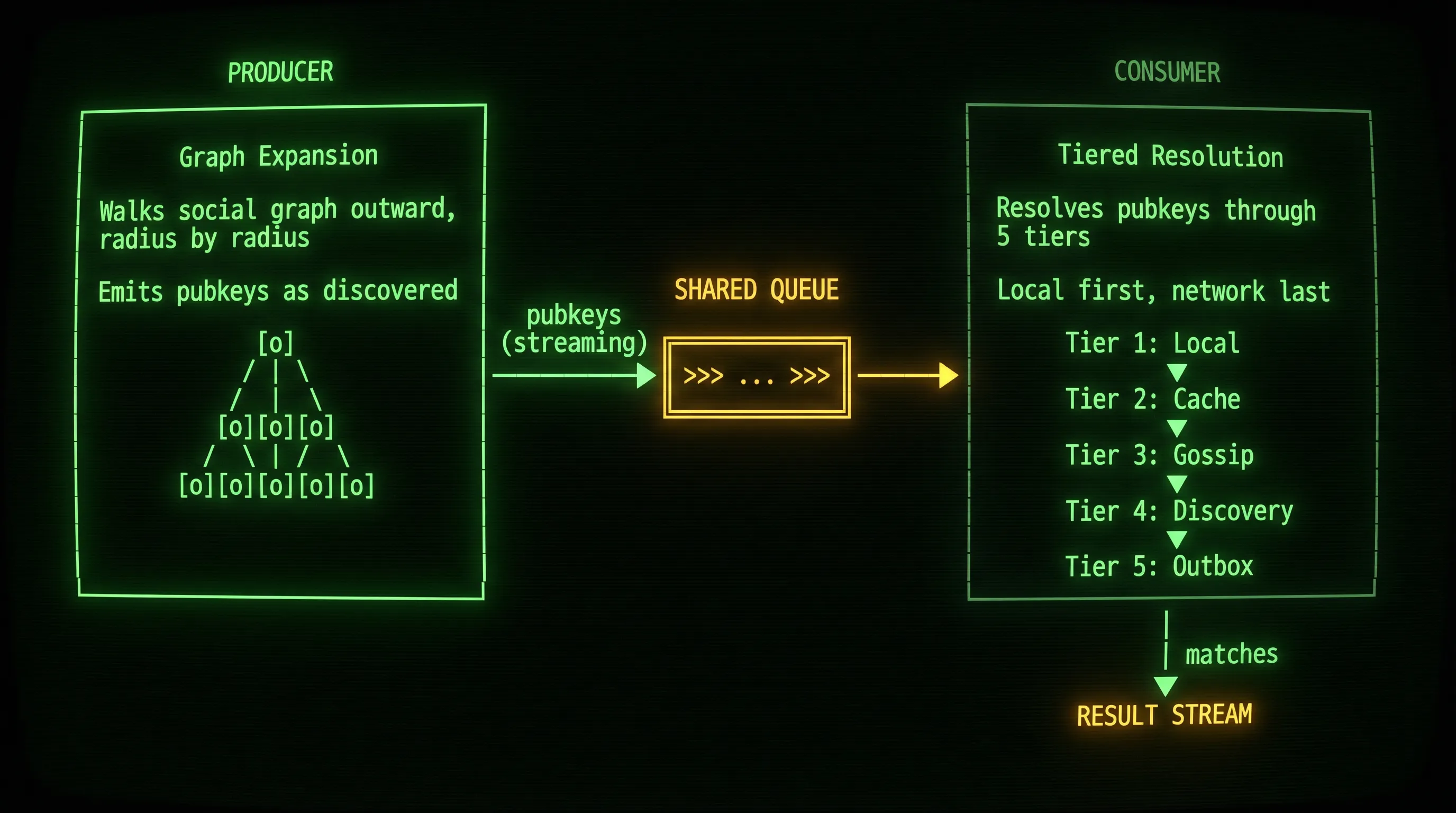

The second iteration was a near-complete rewrite of the search module. The core idea: split the work into two parallel processes that run simultaneously.

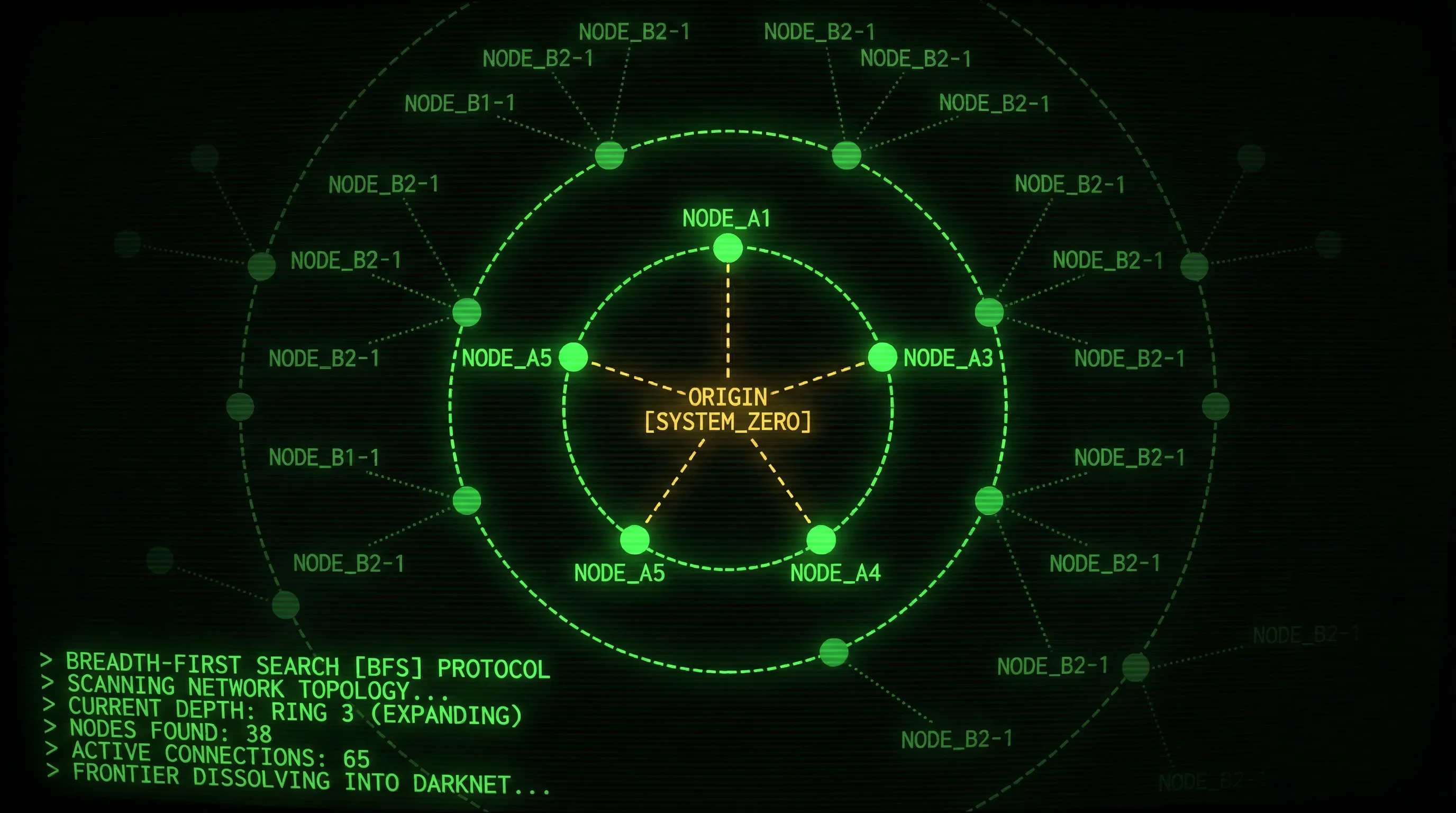

The Producer: Graph Expansion

One process is dedicated entirely to expanding your social graph. Starting from your follow list, it walks outward: fetching each contact’s follow list, then their contacts’ follow lists, and so on, up to a configurable maximum radius. Each time it discovers new pubkeys at a given distance, it pushes them into a shared queue.

This runs continuously in the background. It doesn’t care about the search query. It’s just building a wider map of your social neighborhood and caching the results for the consumer to use.

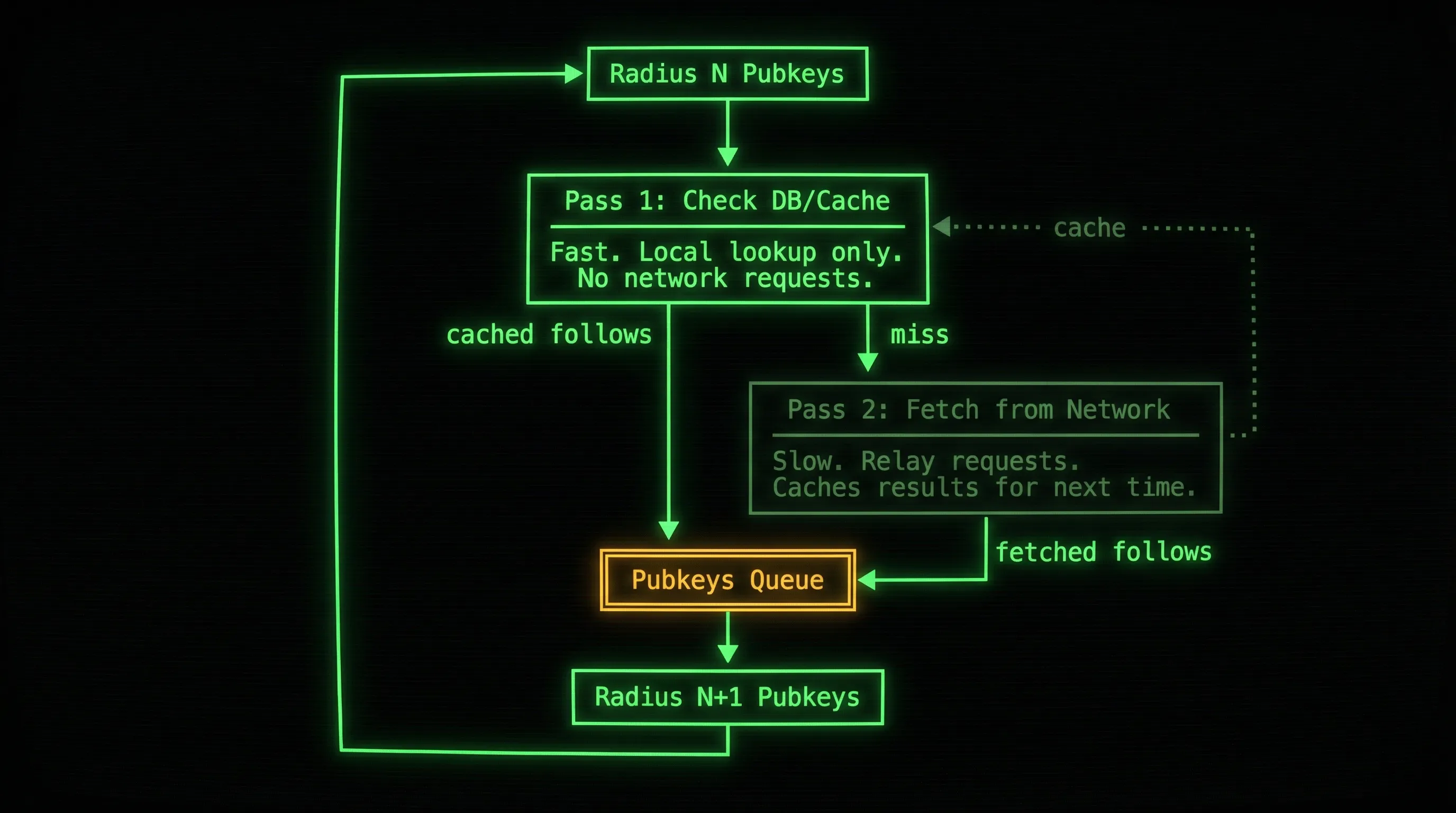

The producer itself does two sequential passes for each radius level:

Pass 1 is fast: it checks locally for follow lists we already have stored (we already stored the follows of the signed-in users). Pass 2 only runs for the misses, going to the network to fetch follow lists we haven’t seen before. Because Pass 1 can push pubkeys into the queue without doing any network requests, the consumer can begin resolving matches right away while the producer continues expanding the graph on pass 2. The producer can move through cached regions of the graph almost instantly and only slows down at the edges where it hits the network.

The Consumer: Tiered Resolution

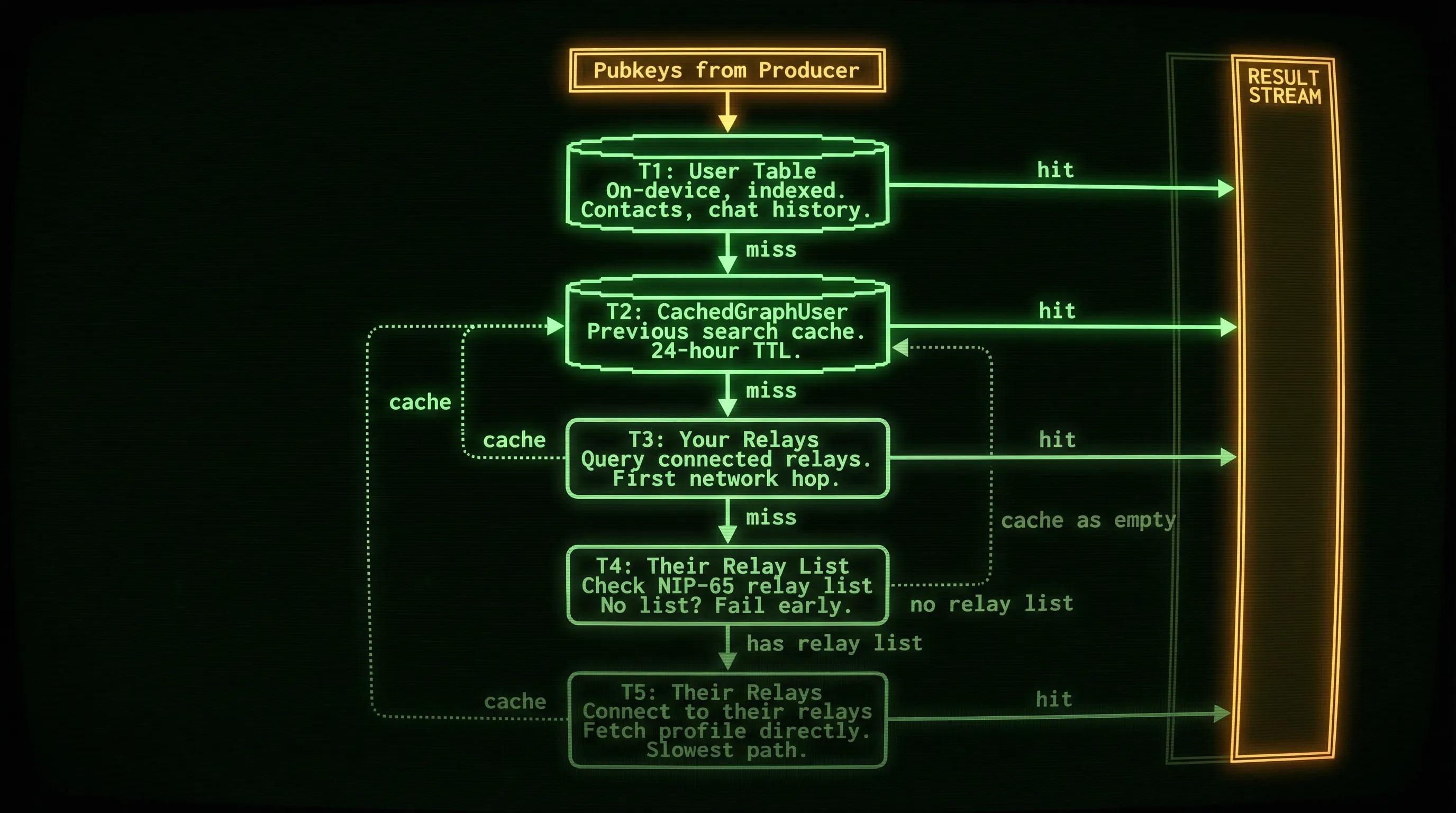

The other process is the one that actually answers the query. It pulls from the graph the producer is building and resolves matches through a series of tiers, from fastest to slowest:

Tier 1: What we already know. The app already maintains a User table for normal operation (people you’ve chatted with, contacts you’ve added). We search this first. It’s on-device and indexed. We’re already syncing the metadata for these pubkeys, so we can resolve matches immediately.

Tier 2: What we’ve seen before in search. Searches populate a CachedGraphUser table with profiles fetched from relays in earlier sessions, stored with a 24-hour TTL. If you searched for “Alice” yesterday, her profile might still be cached, even if you search for a different user today, the social graph is likely mostly unchanged. This is still a local lookup, still fast.

Tier 3: Ask your relays. If a pubkey from the producer’s queue isn’t in either local table, we fetch their kind:0 metadata from the relays we’re already connected to. This is the gossip approach: query relays you know about and hope they have what you’re looking for. It’s the first time we touch the network, but at least we’re using connections that already exist.

Tier 4: Look up their relays. If our relays don’t have the profile, we switch to the outbox model: check whether the user has published a relay list (NIP-65 relay list metadata). If they haven’t, which is common for inactive or poorly configured accounts, we fail early and move on. No point opening connections to relays that don’t exist.

Tier 5: Fetch from their relays. If they do have a relay list, we go to the source: connect to their declared relays and fetch the profile directly. This is the slowest path, since we’re discovering new relay addresses and opening new connections, but also the most thorough.

Why not skip straight to the outbox model? Speed. The outbox approach requires two round trips: one to fetch the user’s relay list, another to fetch their profile from those relays. If our connected relays already have the profile, we save one network request.

The diagram shows a single pubkey flowing through the tiers, but in practice the consumer processes pubkeys in batches. Tiers 1 and 2 are local lookups, so they run through the entire batch quickly. The misses from Tier 2 get handed to Tier 3, which fires off concurrent requests to your connected relays for the whole batch at once. Misses from Tier 3 flow into Tier 4, and those that have relay lists move to Tier 5, again with concurrent network requests. So at any given moment, Tier 3 might be fetching profiles for one batch while Tier 5 is still resolving the previous batch’s stragglers. The tiers don’t block each other.

The consumer streams results to the UI as they’re found at each tier. It deduplicates by pubkey, so if Tier 1 already found “Alice,” it won’t even get to Tiers 2-5. And if the user changes their query, both the producer and consumer cancel immediately. No wasted bandwidth on stale searches.

Benchmarking

I added per-tier metrics (items received, matches found, fetch timing for the network tiers) behind a feature flag, and wrote benchmarks that measured time-to-first-result and time-to-target for cold and warm searches.

Here’s what a real benchmark run looks like. Cold search (no cache, first time searching):

Producer: 927 pubkeys emitted

Tier 1 (User table): 927 in -> 0 found, 927 fwd

Tier 2 (Cache): 927 in -> 0 found, 927 fwd

Tier 3 (Network): 927 in -> 877 found, 50 fwd

Fetches: 7 total, avg 769.9ms, max 1.07s

Tier 4 (Relay lists): 50 in -> 7 has-relays, 43 cached-empty

Fetches: 6 total, avg 494.6ms, max 704.1ms

Tier 5 (User relays): 7 in -> 0 found

[Cold] target=2.05s, first_result=2.05s, complete=3.13s

927 pubkeys flow through the pipeline. Tiers 1 and 2 find nothing (empty cache), so all 927 hit the network at Tier 3. Of those, 877 are resolved from my connected relays. The remaining 50 go to Tier 4, where 43 have no relay list (cached-empty, fail early) and only 7 have relays to try. Total time: about 3 seconds.

Now the same search again, warm (cache populated from the cold run):

Producer: 927 pubkeys emitted

Tier 1 (User table): 927 in -> 0 found, 927 fwd

Tier 2 (Cache): 927 in -> 877 found, 0 fwd

Tier 3 (Network): 0 in

Tier 4 (Relay lists): 0 in

Tier 5 (User relays): 0 in

[Warm] target=9.71ms, first_result=9.71ms, complete=18.77ms

Same 927 pubkeys, but now Tier 2 catches 877 of them from cache. Tiers 3-5 see zero traffic. Time-to-target drops from 2 seconds to 10 milliseconds. (If you’re wondering what happened to the 50 pubkeys, none of them had metadata so we cached them as empty.)

Without this kind of visibility, I was guessing. When everything runs concurrently across a producer and five tiers of consumer, intuition only gets you so far. Every optimization after that, batch size, concurrency control, timeouts, came from what the numbers told me.

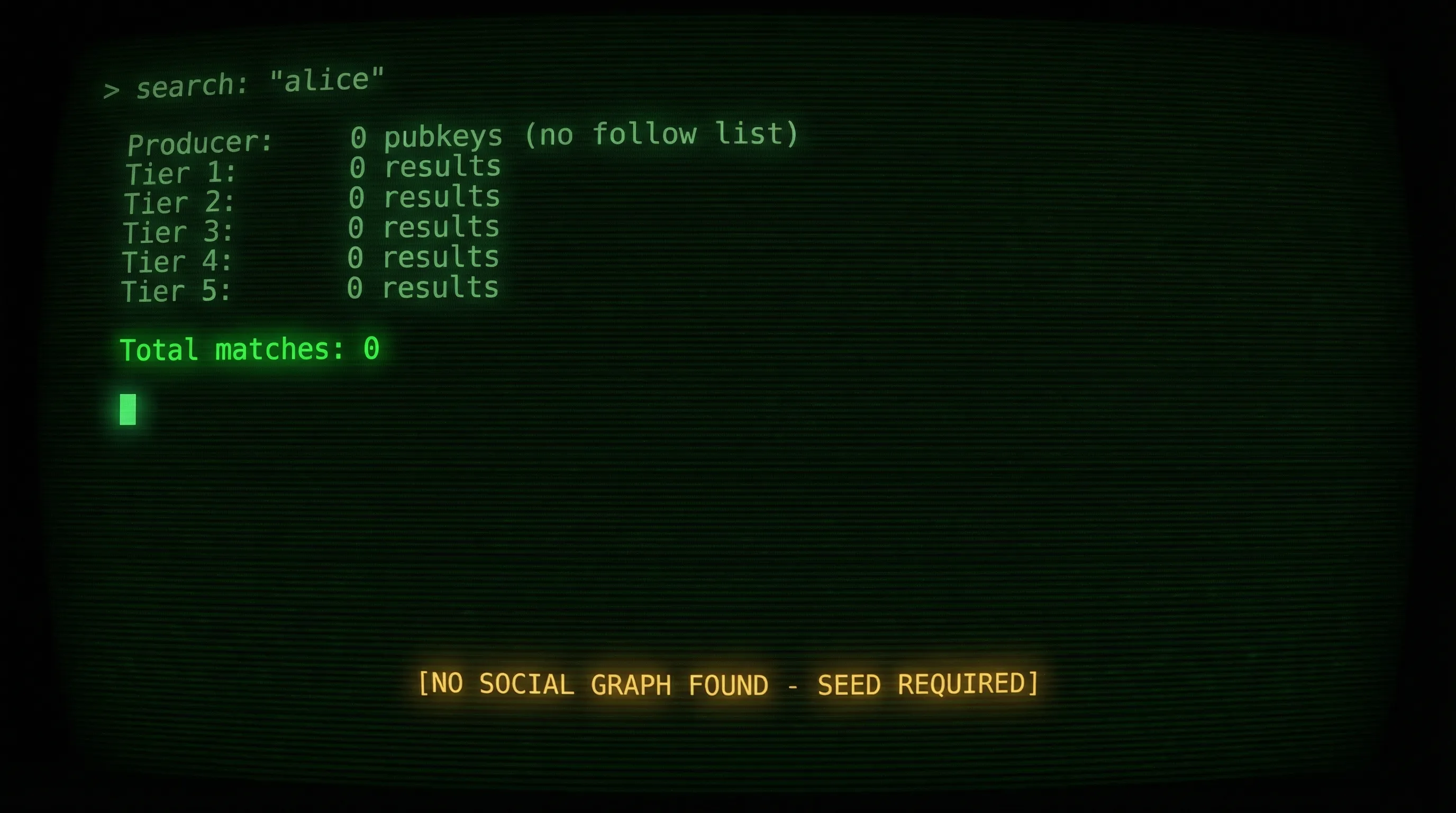

The Edge Case: Empty Graphs

Imagine someone downloads White Noise, generates a fresh keypair, and the first thing they do is search for a friend to message. They have no contacts, no follow list, no history. Just a brand new identity on the network.

The entire architecture falls apart here. The producer has no follow list to expand. The consumer’s local tiers are empty. Tiers 3-5 have no pubkeys to look up. Every tier returns nothing because there’s nothing to traverse.

After discussing a couple of different approaches with the team, I ended up adding fallback seed injection. When the graph is exhausted or empty, I inject a well-connected pubkey as entry point, bootstrapping a temporary graph so the search has something to traverse. It’s not perfect (the results aren’t personalized), but it means new users don’t stare at an empty screen.

Beyond Follows: Groups as Social Signal

Up to this point, the social graph was built entirely from follow lists. But White Noise is a chat app, and the people you chat with in groups are a strong signal of who you might want to find, even if you don’t explicitly follow them.

I added group co-member injection to the producer: at radius 1, alongside your direct follows, we inject the pubkeys of everyone you share a group with. This data is already local (we have the group membership on-device), so it adds zero network overhead. A colleague you’ve been messaging in a group chat now shows up in search results at the same priority as someone you follow, without either of you needing to follow the other.

The broader insight: in a decentralized protocol, the “social graph” doesn’t have to mean just the explicit follow list. Any relationship the app already knows about is a signal worth using.

What I Learned

These iterations on user search taught me a few things about building on nostr:

Local first isn’t optional. If you have data on-device, show it immediately. Users will tolerate results trickling in from the network, but they won’t tolerate an empty screen while you wait for relays.

Cache aggressively, expire gracefully. Every profile you’ve seen before is a local lookup you don’t have to make over the network.

When in doubt, instrument. I couldn’t improve what I couldn’t measure. Adding per-tier metrics is what let me iterate quickly, even though users never see them.

Design for the empty state. The hardest users to serve aren’t your power users with rich social graphs. They’re the new users with nothing. If your architecture assumes data exists, you need an explicit fallback for when it doesn’t.

The full implementation is in the White Noise Rust crate:

- PR #470: User search - first implementation

- PR #498: Fix the performance of user search - the rebuild

- PR #506: Include connected relays in fallback - relay connectivity fix

- PR #509: User search fallback - empty graph fallback

- PR #510: Include group co-members - groups as social signal